©Moronic Ox Literary Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books

Essay

Who Drew the Borders Anyway?

David H. Mould

Since my childhood travels with my parents and sister in Western Europe, I've always been fascinated by borders. My interest intensified in my undergraduate program in European Studies. The history courses were served up in predictable chronological slices, starting with the so-called Middle Ages and proceeding through the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution and the wars and revolutions of the 19th century all the way to World War Two. Our textbooks often had the word “age” in the title—the “Age of the Bourgeoisie,” the “Age of the Puritans,” the “Age of Revolution,” and so on.

In line with current academic trends, the temporal slices came with toppings of social and economic history, but the basic recipe was military and political. It was a long list of wars fought between empires, kingdoms and principalities, or between religious factions, rebellions by nobles, peasants and workers, ceasefires and treaties, an endless succession of kings, queens, regents, prime ministers and rebel warlords, and just too many dates to remember. The British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, author of the sweeping 12-volume The Study of History (published over a quarter of a century) has the misfortune to be credited with the memorable phrase that history is “just one damned thing after another.” In fact, Toynbee believed exactly the opposite and used the phrase to critique other historians, who chronicled events but failed to analyze connections between them. For Toynbee, history was all about grand patterns, the rise and fall of world civilizations that transcended nations, races, dynasties, conflicts and changing borders.

I have some sympathy with the “just one damned thing after another” complaint because in order to present the big picture, the grand patterns in history, you need to know the small stuff. Besides all the dates and names, historians face daunting cartographic challenges. As all those empires, kingdoms and principalities fought, made peace and fought again, the maps kept changing as they grabbed portions of each other’s territory. I had to remember and date the changing borders of the Holy Roman, Austro-Hungarian, Napoleonic and Ottoman empires, Bismarck’s Germany, the shifting front lines of World War One, the faster moving battle maps of World War Two. Some areas of the map seemed to be constantly changing hands and color. One of my fellow students reached metaphorical exhaustion in a term paper when he described Alsace Lorraine, repeatedly fought over by France and Germany, as “the innocent filling between two hostile slices of bread.”

It was challenging enough to keep up with the shifting borders of European countries. When I opened the atlas and turned to other continents, the borders of some countries seemed to make no sense at all. Why were some strangely shaped, with portions of their territory protruding into other countries? Why were there straight-line borders, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa? Who on earth drew the borders this way, and why?

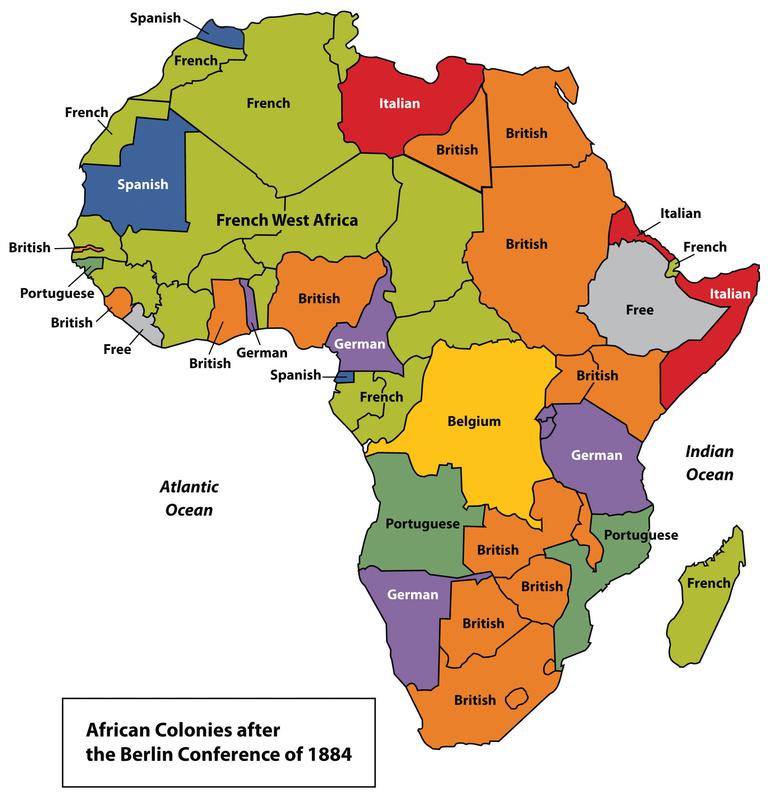

Mostly it was political leaders sitting around conference tables in European capitals, thousands of miles away from the lands they were dividing. The so-called “Scramble for Africa” began with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, where Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Italy and the Ottoman Empire, each with its economic and geo-political goals, carved up the continent into spheres of influence.

SUBMISSIONS

Moronic Ox Literary and Cultural Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books Advertise your book, CD, or cause in the 'Ox'

Novel Excerpts, Short Stories, Poetry, Multimedia, Current Affairs, Book Reviews, Photo Essays, Visual Arts Submissions

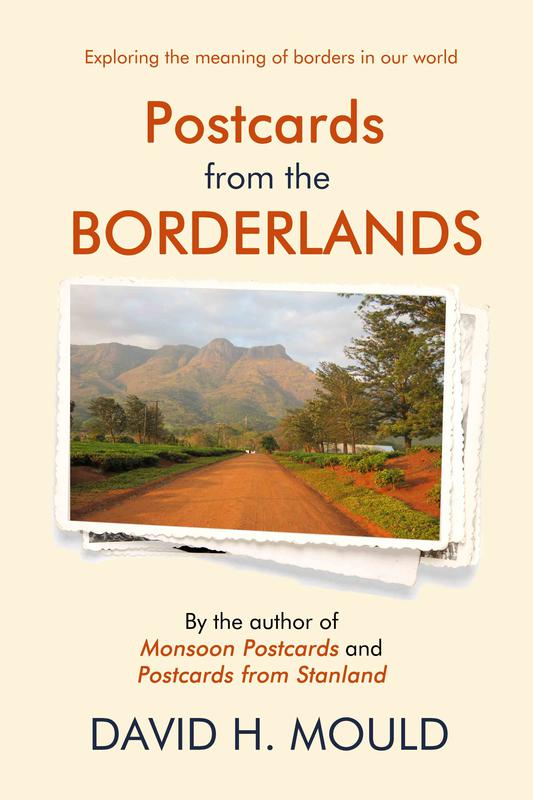

Exploring the meaning of borders in our world. What are borders? Are they simply political and geographical, marked by posts, walls and fences, or should we think of them more broadly? Consider the borders within countries, determined by race, ethnicity, or caste. Borders may be physical and economic, and even perceptual—the borders of our minds. In Postcards from the Borderlands, historian and journalist David Mould rambles through a dozen countries in Asia, Southern Africa and Eastern Europe by car, bus, train, shared taxi and ferry, exploring what borders mean to their peoples. Mould finds topics of interest even in the most ordinary places—an airport departure lounge, a food court, a roadside restaurant, a government office. Every road trip offers a moving window display of landscape features, crops, livestock, houses, churches, temples, mosques, schools, factories, military bases, vehicles. He notes what people are selling on the roadside and the markets, the restaurant menu, the indecipherable instructions for the TV remote in his hotel room. What people wear. What they eat. How they talk to each other. The questions they ask him. The questions he asks them. Away from the tourist hotspots, he finds that it is often the commonplace that is most fascinating and revealing of culture.

Click Cover to Purchase

Postcards from the Borderlands [is] gracefully interwoven with history and geography, and guaranteed to ignite a bit of wanderlust in anyone who shares Mould’s sense of wonder and adventure at our strangely eclectic world of borders.

-Natalie Koch, Associate Professor of Geography, Syracuse University, New York

Mould is an intrepid traveler, often poking his nose in where it isn’t welcome. We see a style of travel that requires a certain toughness and resolution, but which rewards Mould, and his readers alike, with secrets invisible to conventional tourists.

-Alan Wilkinson, biographer, travel writer and novelist, Durham, UK

Postcards from the Borderlands is a love letter to the world by an “accidental” travel writer.

-Jean Andrews, award-winning video documentary producer and science writer.

Over the next half century, cartographic surveys and boundary commissions created the borders that were preserved intact when the countries became independent. They cut across topography, ancient kingdoms, ethnic groups, and traditional hunting and grazing lands. As British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury famously remarked at the signing of the Anglo-French convention on the Nigeria-Niger boundary in 1906: “We [the British and the French] have been engaged in drawing lines upon maps where no white man’s foot ever trod: we have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediments that we never knew exactly where the mountains and rivers and lakes were.”

It may seem obvious, but it’s worth stating anyway. Except for a few mountain ranges and wide rivers, there are few natural land borders anywhere in the world. A border, by its very nature, is demarcated by someone or something—a cartographer or surveyor, a national government, an international agency, a military force, a border commission. The act of demarcation inevitably gives rise to disputes. Borders, especially those with walls and fences, create economic and social barriers, dividing ethnic and religious groups, communities and even families. For aggressive nation-states (I was not thinking of Russia when I first wrote this, but now I am), the lines on the maps are never fixed or accepted; they simply represent a fragile status quo that can be disrupted by war, economic blockade, or diplomacy.